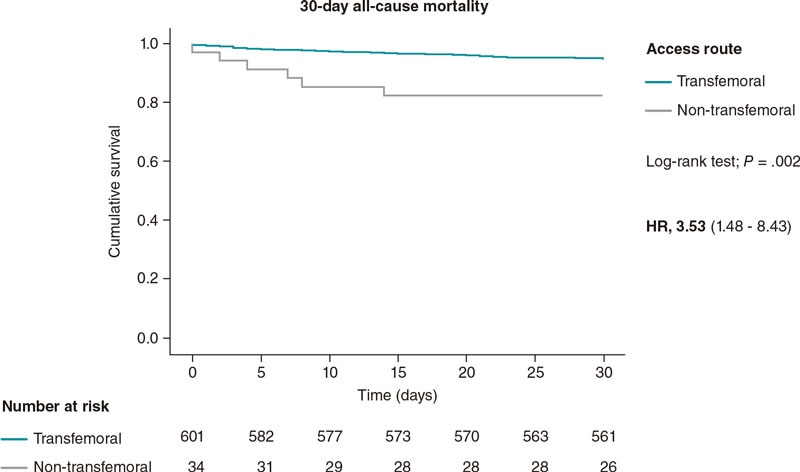

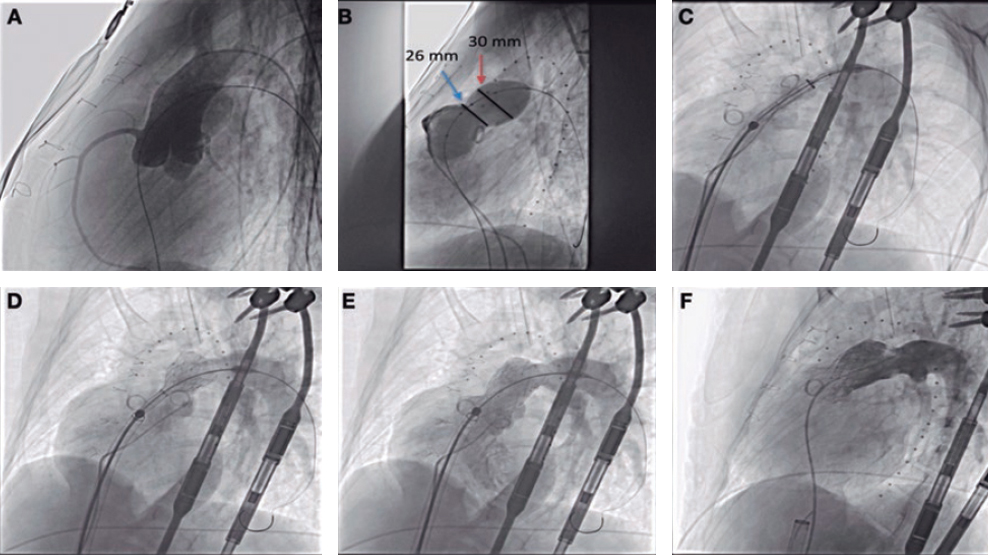

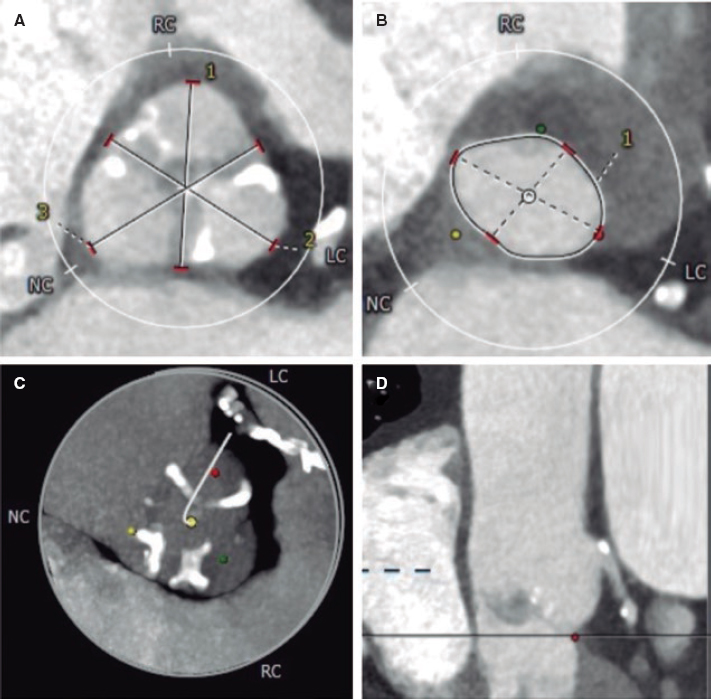

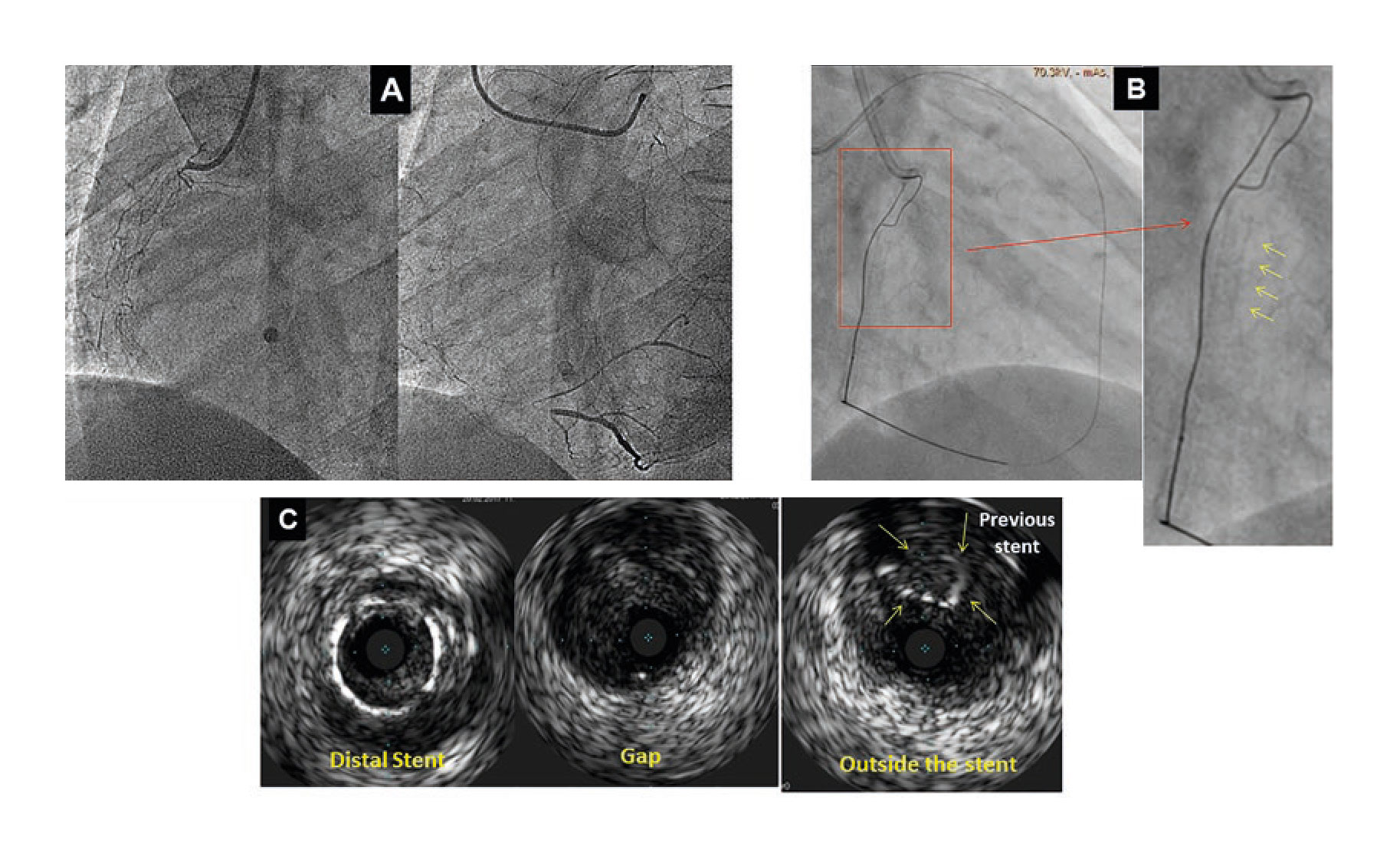

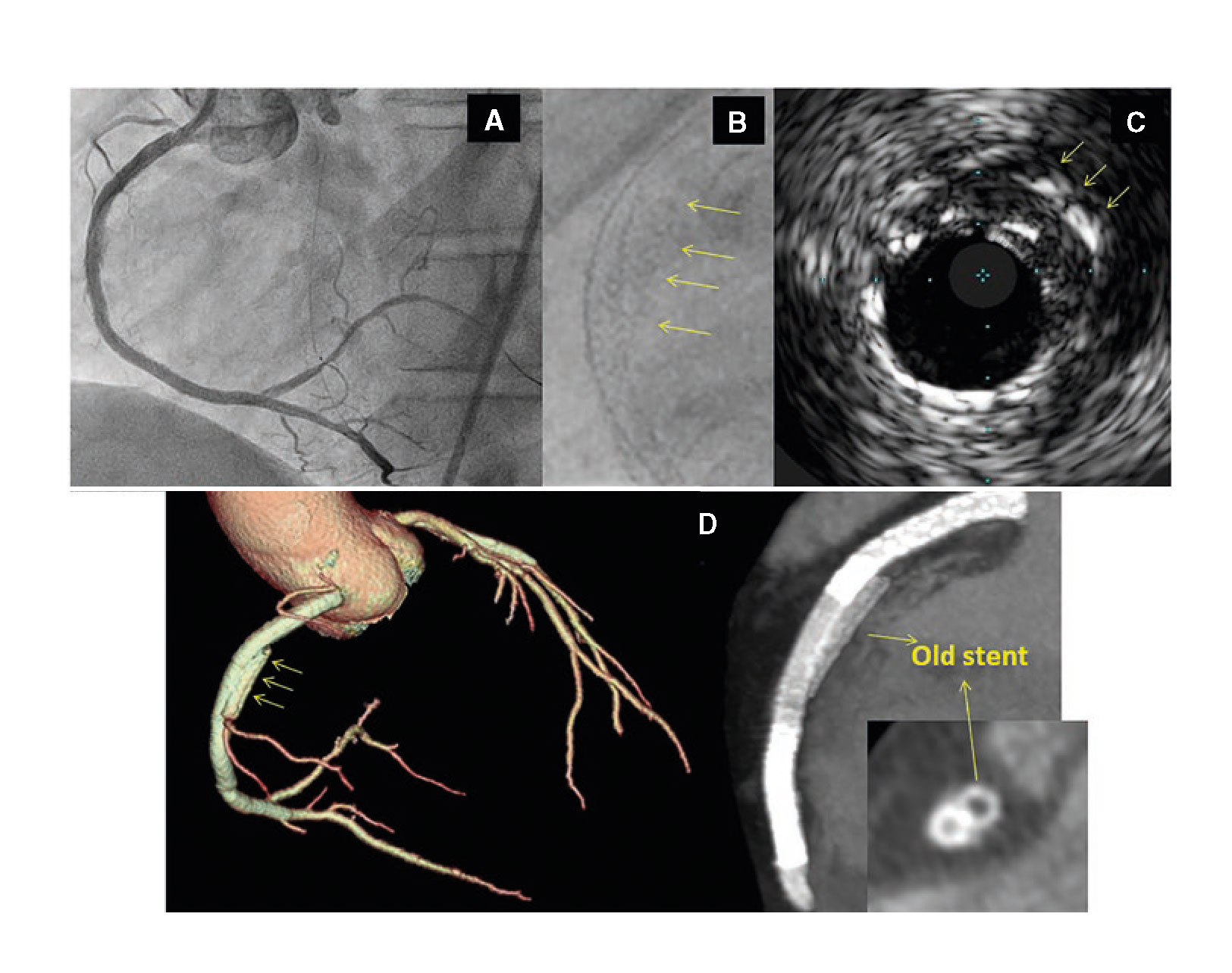

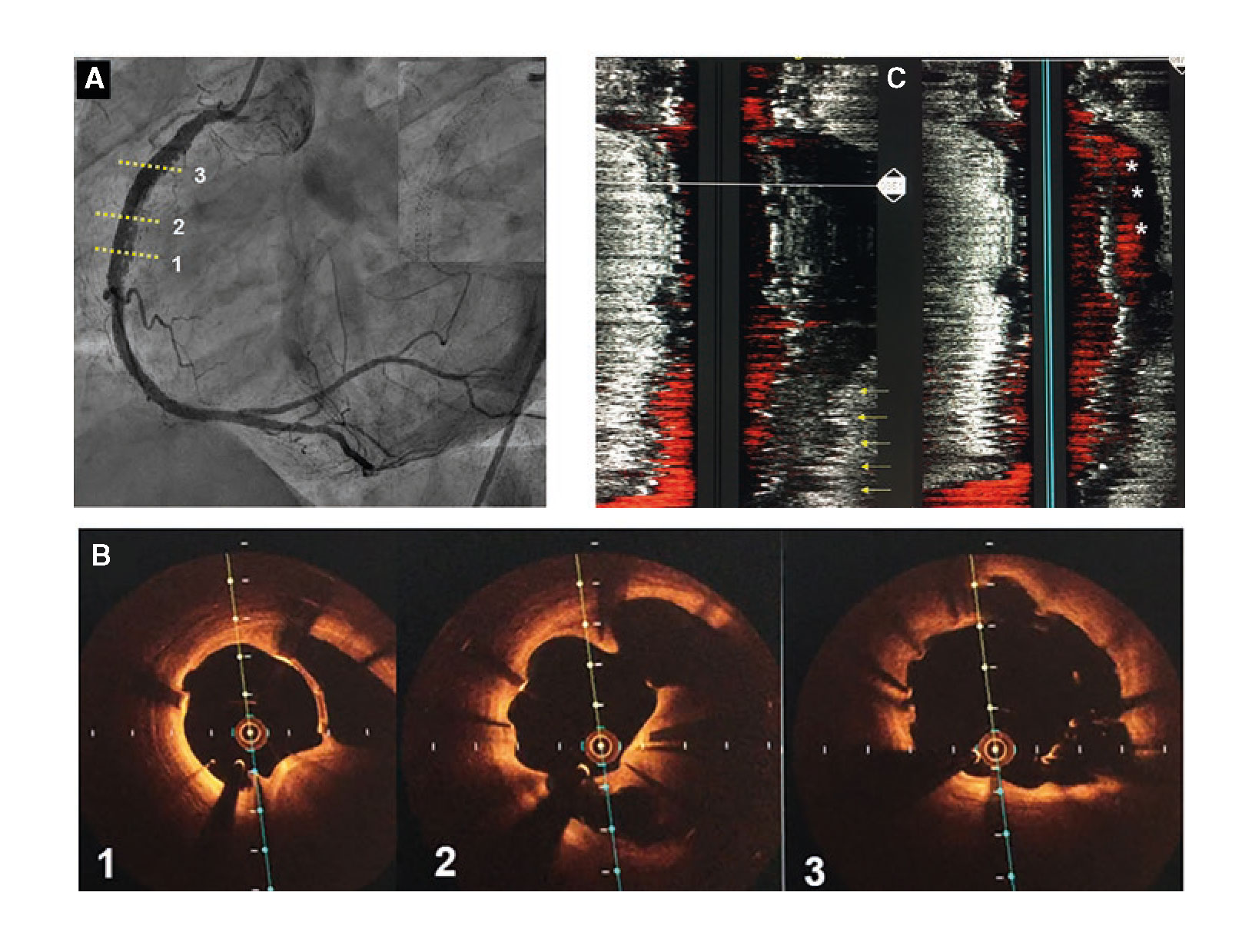

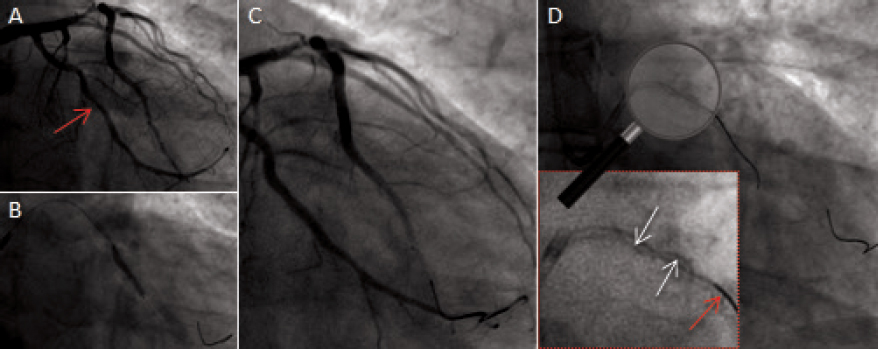

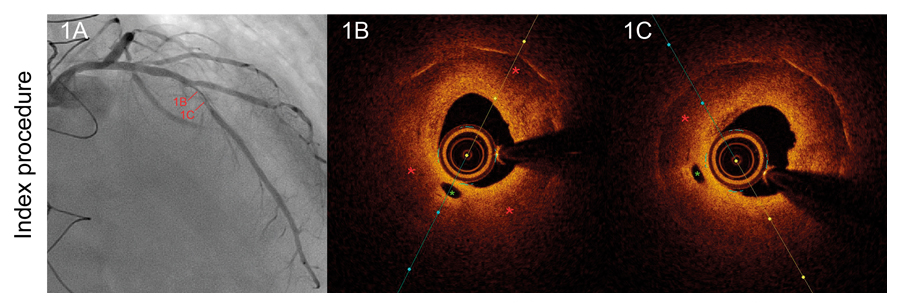

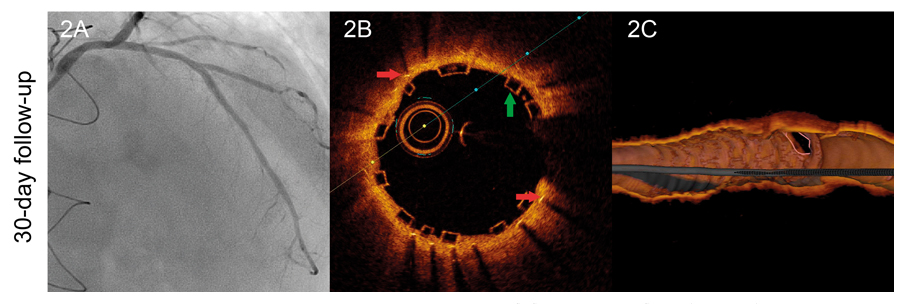

A 48-year-old male was admitted to the hospital due to stable angina. The coronary angiography showed a very long in-stent coronary chronic total occlusion in his right coronary artery (RCA) (figure 1A). We attempted the retrograde access following failed antegrade access. At mid-RCA level, the guidewire was advanced outside the stent (arrows) (figure 1B). The intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) conducted confirmed the correct position of the guidewire at the stent distal edge. However, in the gap between both stents, the guidewire was advanced to the subadventitial space and maintained this position along the full length of the proximal stent (arrows) (figure 1C). After predilation, 3 drug-eluting stents were successfully implanted (figure 2A). A double stent can be seen in the angiographic and IVUS images obtained (figure 2B and figure 2C): the previous (arrows) and the newly implanted stent. The computed tomography scan conducted 3 months later confirmed the exclusion of the old stent (arrows) from the coronary flow and the patency of the stents implanted in the subadventitial space (figure 2D). Six months after the index procedure, a new angiographic assessment confirmed the long-lasting good results (figure 3A). However, the optical coherence tomography showed significant late-acquired stent malapposition (figure 3B). The IVUS longitudinal views showed the old occluded stent (arrows) and, on the other plane, the stent malapposition (asterisks) (figure 3C), probably due to the hematoma reabsorption induced during the recanalization process. The patients remained asymptomatic. It was decided to maintain aspirin and ticagrelor until the next reassessment scheduled after an 18-month follow-up.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Corresponding author: Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Reina Sofía, Avda. Menéndez Pidal s/n, 14004 Córdoba, Spain.

E-mail address: soledad.ojeda18@gmail.com (S. Ojeda).

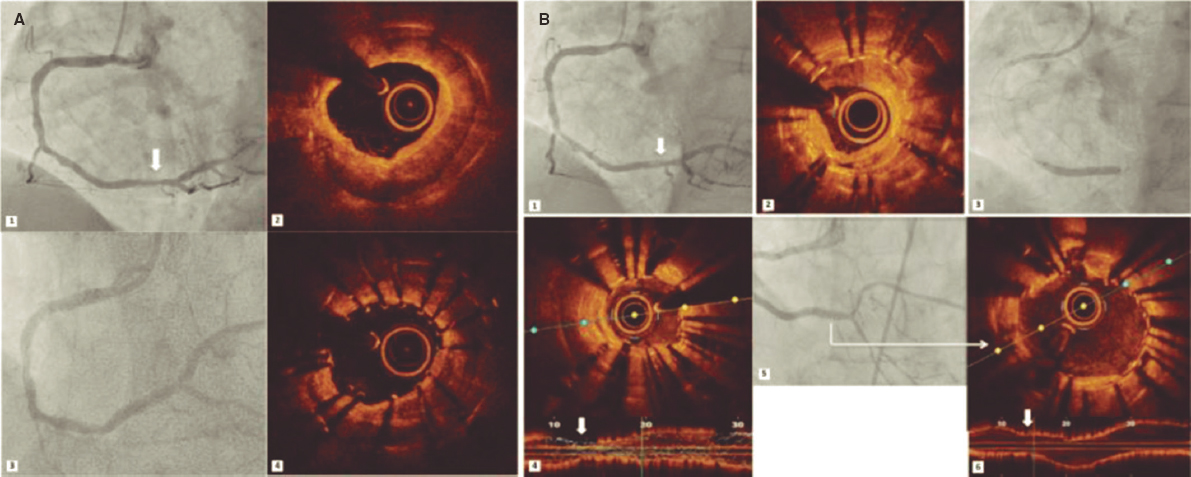

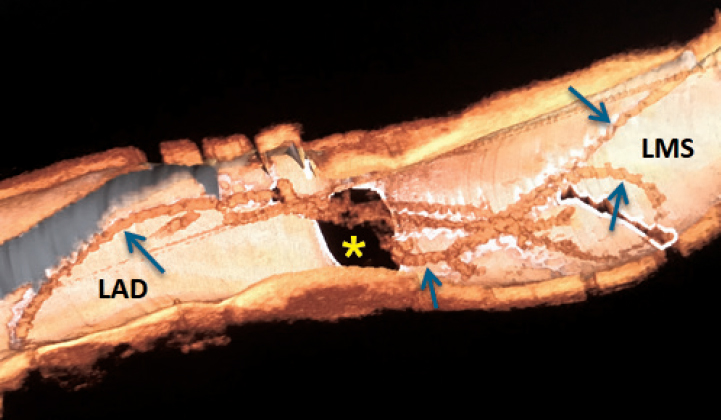

One 72-year-old male who recently suffered from a non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) underwent a staged percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) due to significant stenosis of his mid left anterior descending (LAD) and mid left circumflex (LCX) arteries (figure 1A; red arrow). After placing one hydrophilic Hi-Torque intracoronary guidewire into the LCX, one drug-eluting stent (DES) was deployed uneventfully (figure 1B and figure 1C). However, we were unable to extract the guidewire afterwards probably due to entrapment with a calcified plaque. The stronger traction resulted in the partial fracture of the guidewire followed by the disruption of the coils (figure 1D, white arrows; the red arrow points to a second inserted guidewire). Retrieval was unsuccessfully attempted using different techniques like the snare loop technique and the twisting wire technique (video 1 of the supplementary data). After the uncomplicated stenting of the mid LAD, we conducted an optical coherence tomography (OCT). A three-dimensional reconstruction showed remains of the broken wire (figure 2; blue arrows) coming out of the LCX (figure 2; yellow asterisk) and into the left main stem (LMS) and proximal LAD with presence of adhered and free-floating thrombotic material as shown in the cross-sectional views (figure 3A and figure 3B; blue arrows point to the wire remains; the yellow arrow points to the thrombotic material; MLA, minimal lumen area; video 2 of the supplementary data). We immediately proceeded to eliminate the uncoiled filaments from the circulation by deploying one DES into the distal LMS and the proximal LAD. The control OCT conducted showed the wire remains trapped by the struts of the stent against the vessel wall (figure 3C; white arrow: wire remains, highlighted in red-framed box; red asterisks: stent struts).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Video 1. Leithold G. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M19000020

Video 2. Leithold G. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M19000020

Corresponding author: Departamento de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Carretera Madrid Cartagena s/n, 30120 El Palmar, Murcia, Spain.

E-mail address: gunnar.leithold@gmail.com (G. Leithold).

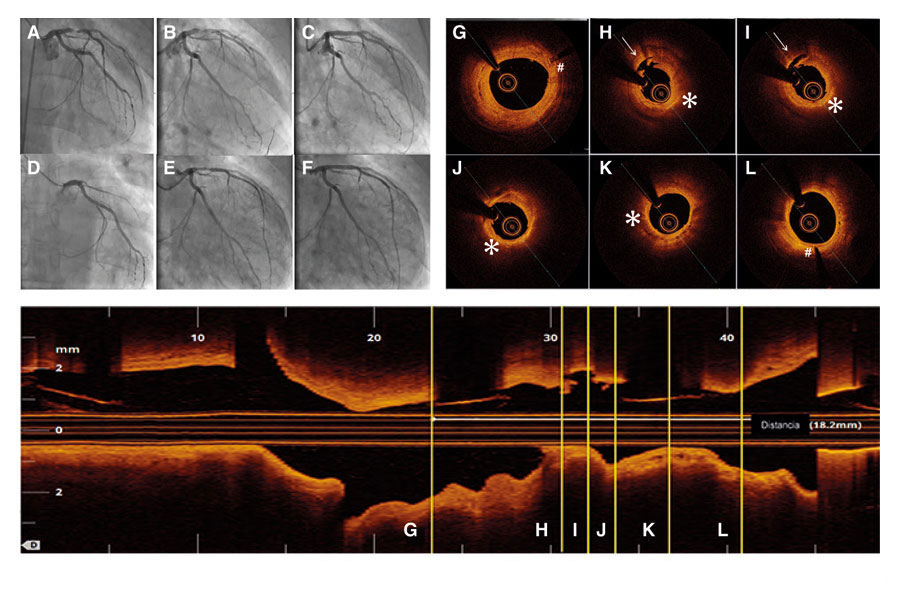

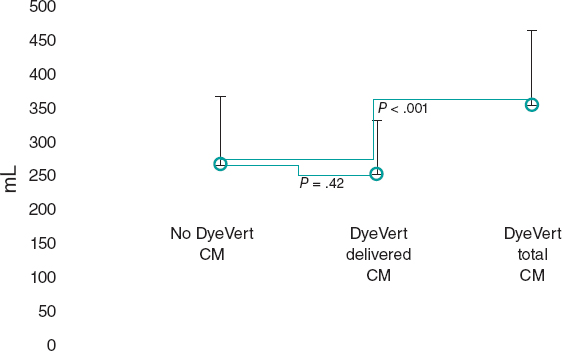

Sixty-four year-old male patient with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction due to occlusion of his anterior descending artery who received one 3 × 18 mm direct bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS) (figure 1A-C). Then he received acetylsalicylic acid and atorvastatin.

Fifty-two months later he experienced an anterior reinfarction due to the occlusion of the same segment of the anterior descending artery. Thrombo-aspiration with flow recovery (figure 1D-E) was conducted and the optical coherence tomography showed strut remnants almost indistinguishable in the BVS segment. Thrombosis was attributed to a tear in the neoatherosclerotic lipid plaque (figura 1H-I, video of the supplementary data). Figures figura 1G-L show the BVS markers (pound sign) and the presence of the aforementioned torn lipid plaque (asterisk and arrow, respectively). One drug-eluting metallic stent was implanted inside the stent (figura 1F).

Figure 1.

The primary goal of BVSs is to eliminate the risk of very late thrombosis once the device is gone. In several series of very late thromboses in drug-eluting metallic stents, one of the main causes seen in the optical coherence tomography is the tear of the neoatherosclerotic lipid-laden plaque (26% to 31%). Therefore, we should expect a significant drop in stent thrombosis when the BVS process of resorption is complete. However, the restoration of geometry and the arterial vessel-motricity may promote neoatherosclerosis in patients with BVS. As far as we know, this is the very first case of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction induced by a neoatherosclerotic plaque tear 4 years after BVS implantation.

Supplementary data

Video 1. Muntané-Carol G. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M19000018

Corresponding author: Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, Feixa Llarga s/n, 08907 L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain.

E-mail address: gomezjosep@hotmail.com (J. Gómez-Lara).

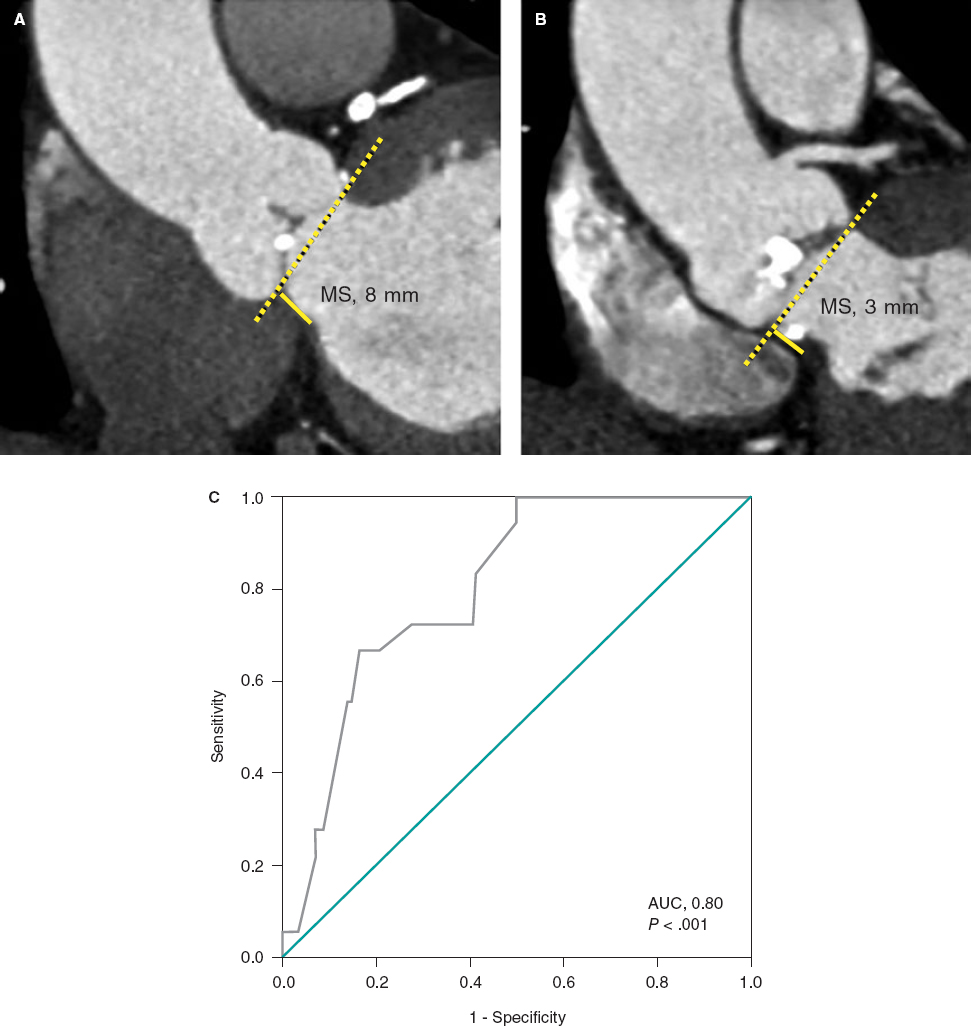

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy is characterized by the absence of lipid-rich plaques. However, transplant recipients may also develop lesions that resemble traditional atherosclerosis. Tacrolimus and everolimus, which are commonly used in transplant recipients, are associated to proatherogenic side effects such as hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia and hypertension. Everolimus also triggers the release of several proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor α. Thus, inflammation, endothelial failure and hyperlipidemia are shared pathophysiological processes common to native in-stent neoatherosclerosis and transplant atherosclerosis.

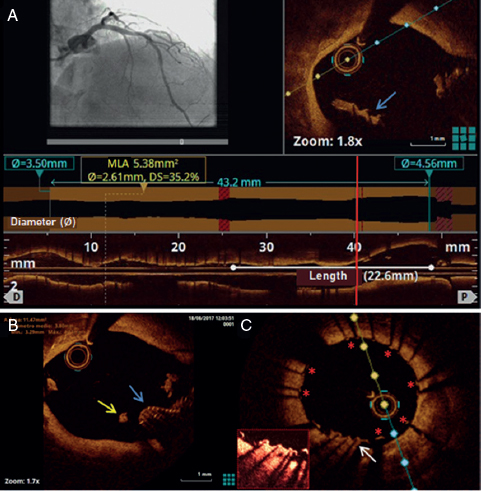

We hereby present the case of a 50 year-old-male with a history of heart transplant 18 years ago with a zotarolimus-eluting stent implanted in his left anterior descending artery 16 months ago. The patient was administered immunosuppressive agents including quad- ruple therapy with corticosteroids, mycophenolate, tacrolimus and everolimus. The patient was admitted to the hospital due to acute heart failure. The coronary angiography conducted showed severe in-stent restenosis (figure 1A). The optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed the presence of early in-stent neoatherosclerosis with lipid-laden plaque similar to the morphological appearance so typical of native neoatherosclerosis (red asterisk) and vasa vasorum (green asterisk) (figure 1B, figure 1C). To avoid multiple metallic layers (red arrows), one bioresorbable vascular scaffold (green arrows) was deployed in-stent. The angiographic and OCT follow-up 1-month later confirmed the presence of scaffold patency with most struts uncovered (figure 2A, figure 2B, figure 2C). This is the first description of in-stent neoathero- sclerosis in a transplant recipient that occurred a few months after deploying the stent. Since the cardiac allograft vasculopathy is often silent and catastrophic, close metabolic control and invasive monitoring through images is advisable in these patients.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Corresponding author: Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, Feixa Llarga s/n, 08907 L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain.

E-mail address: rafaromaguera@gmail.com (R. Romaguera).

Editorials

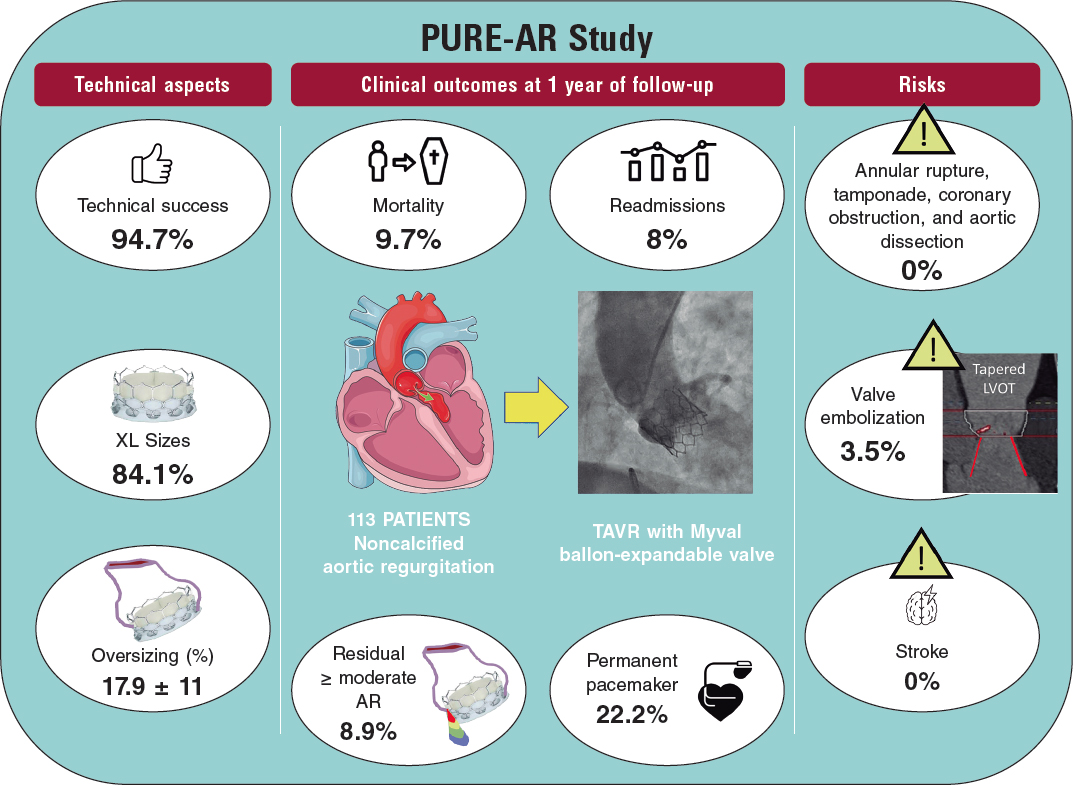

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement for noncalcified aortic regurgitation. Where are we now?

aServicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valladolid, Spain

bCentro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Spain

Original articles

Editorials

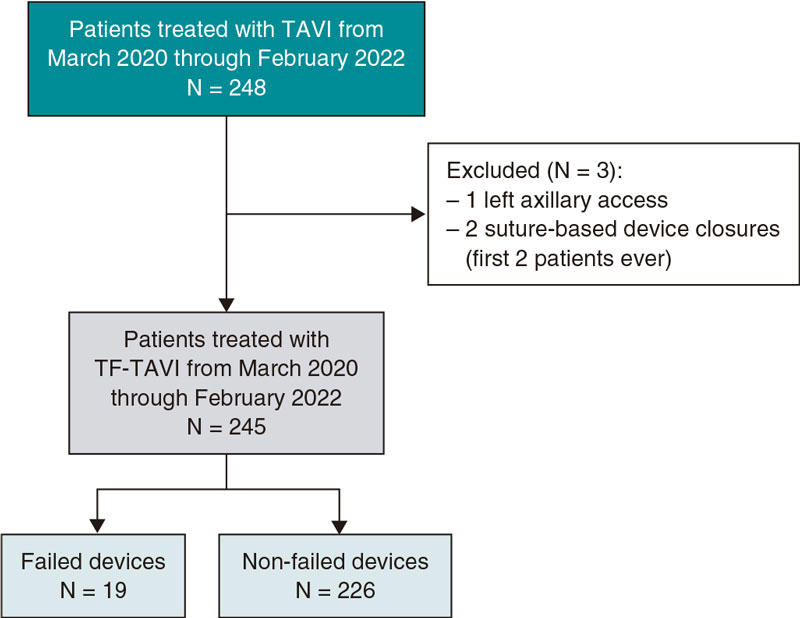

Vascular closure devices: the jury is still out

aUnidad de Hemodinámica, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario Dr. Balmis, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria y Biomédica de Alicante (ISABIAL), Alicante, Spain

bDepartamento de Medicina Clínica, Universidad Miguel Hernández, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis: when should we intervene?

The clinician’s perspective

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain

The interventional cardiologist’s perspective

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo, Vigo, Pontevedra, Spain