HOW WOULD I APPROACH IT?

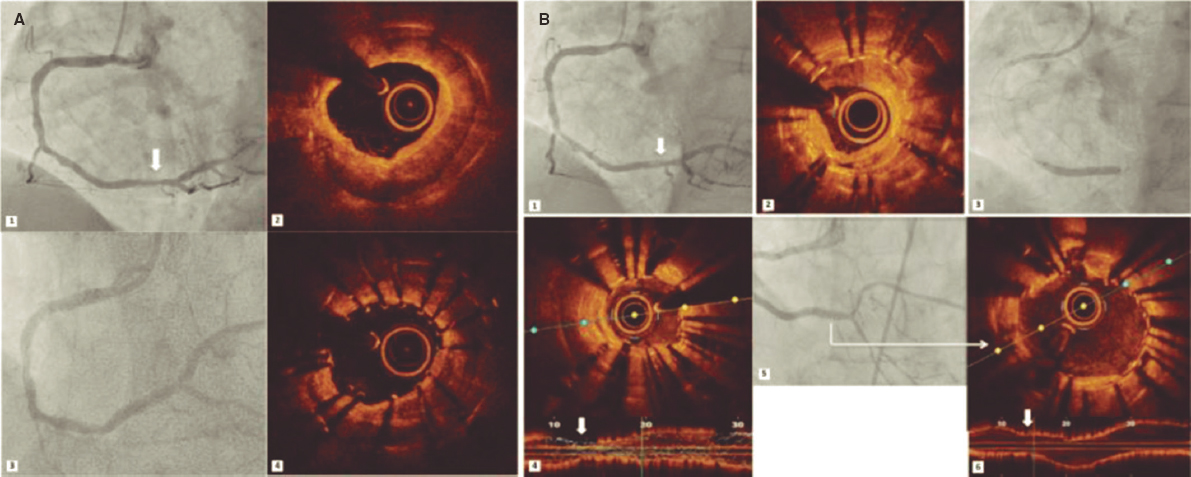

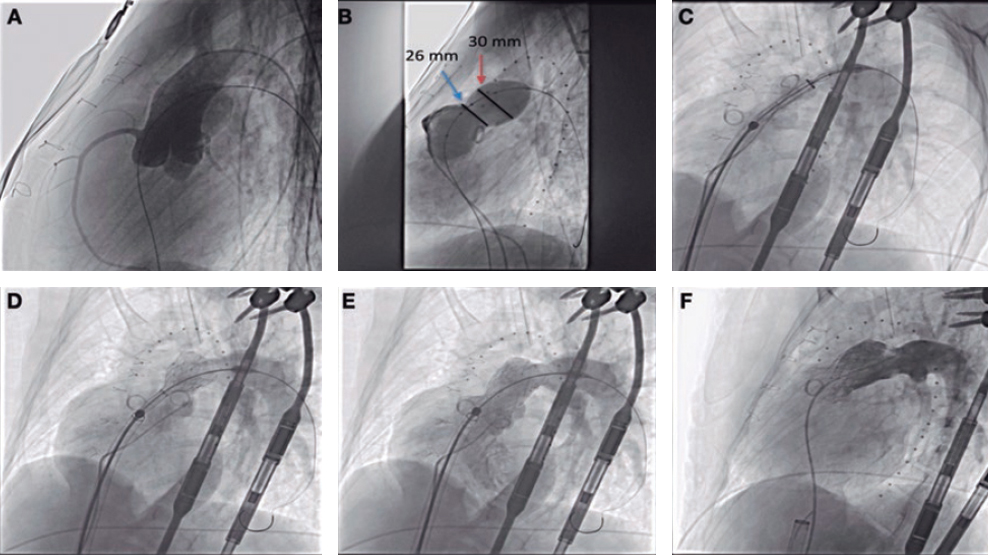

The authors hereby present the clinical case of a 61-year-old male who suffered a seizure in his home, was assessed by the EMT, and then transferred to his reference center where one primary angioplasty was performed with a diagnosis of inferior-lateral ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction in a situation of cardiogenic shock (CS) and further treatment with vasoactive amines and orotracheal intubation. Upon arrival to the cath. lab and since the CS was persistent, as a first-line therapy, it was decided to implant the circulatory mechanical assist Impella CP device (AbioMed, Danvers, Massachusetts, United States). Then a coronary angiography confirmed the embolic occlusion of the circumflex and right coronary arteries that resolved partially after thrombus aspiration and simple angioplasty. However, since hemodynamic instability was persistent and a left intracavitary mass was found on the echocardiography after the interventional procedure, it was decided to remove the Impella CP device and proceed to use extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

This is a very interesting case, not only because finding multiple coronary embolisms as the cause for the CS is exceptionally rare, but also because of the learning we acquired from the initial management of the patient such as:

From the “door to balloon” to the “shock to support”. Considering the patient’s situation when he got to the cath lab, it was prioritized to proceed with the patient’s hemodynamic stabilization through the implantation of the Impella CP device before the interventional procedure (that was performed immediately after device implantation). Although we still don’t have clinical trials that endorse this practice, several authors have confirmed significant mortality rate reductions in patients with CS using a protocol that prioritizes reducing the time elapsed from the medical contact to the implantation of the circulatory mechanical assist device and without significant increases of the time elapsed until the opening of the artery.1

Performing an emergent echocardiography was essential for diagnostic purposes and in order to guide the therapeutic attitude. We should emphasize here that the early echocardiographic assessment of a patient with CS is crucial to be able to rule out any mechanical complications and guide the implantation of a circulatory mechanical assist device.

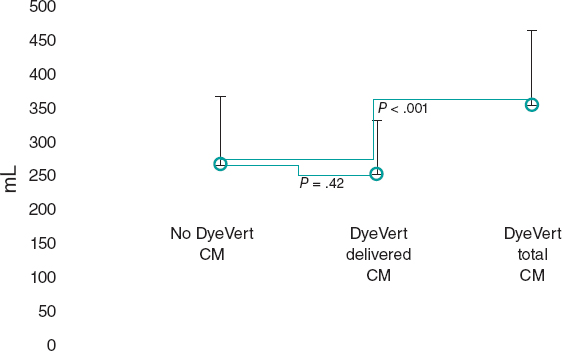

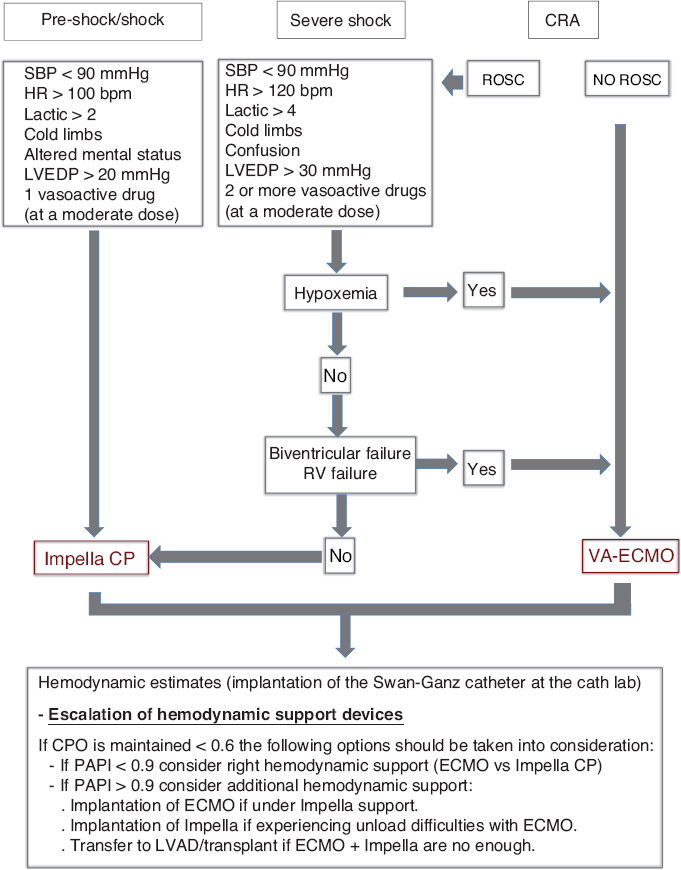

Therapeutic scalation and upgrade. As already described when talking about the evolution of the patient, the persistence of the situation of CS led to a therapeutic scalation from the Impella CP device to ECMO. We should not forget here how important it is to perform an ongoing and thorough assessment of the patient with CS and have action protocols available and adapted to the reality of each particular center (figure 1) in order to offer the best therapeutic option in each particular case.

Figure 1. Action protocol for the management of cardiogenic shock at the Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela, Spain. CPO, cardiac power output; CRA, cardiopulmonary arrest; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HR, heart rate; bpm, beats per minute; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; PAPI, pulmonary artery pulsatility index; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; RV, right ventricle; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Interestingly enough, although in this case finding a mass that was spreading towards the left ventricle led to removing the Impella CP device (due to possible interactions because of its intraventricular location), in patients with CS and severe left ventricular dysfunction, keeping the Impella CP device plus ECMO has proven to be beneficial for prognostic purposes since the Impella CP device is a system to unload the ventricle, and avoid the phenomenon of overload, stasis, and thrombus formation.

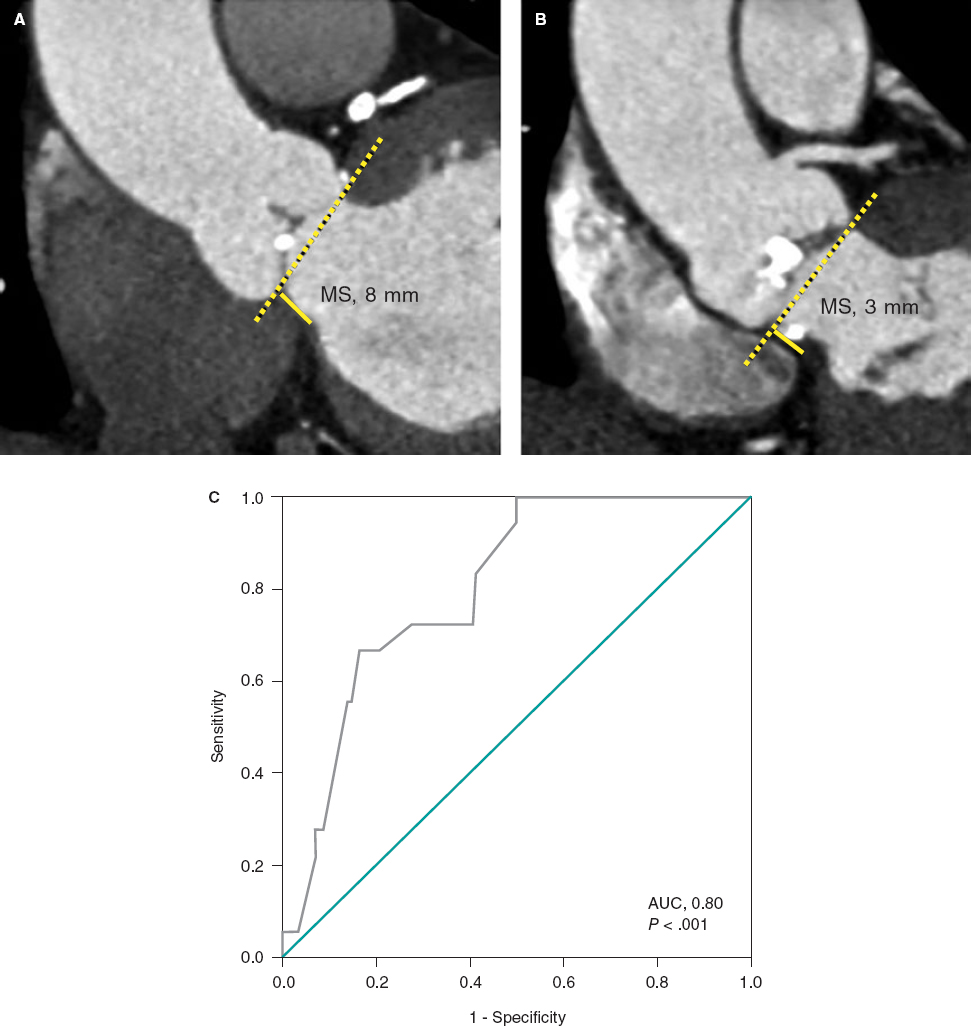

Finally, the computed tomography scan performed on the patient prior to his intensive care unit admission revealed the complete occlusion of different intracranial arteries with diffuse cerebral edema, echocardiographic data of tumor-induced double mitral lesion, and significant systolic dysfunction. At this point, in order to answer the question “how would I approach it?” in a patient with such a complex clinical situation, several issues should be taken into consideration:

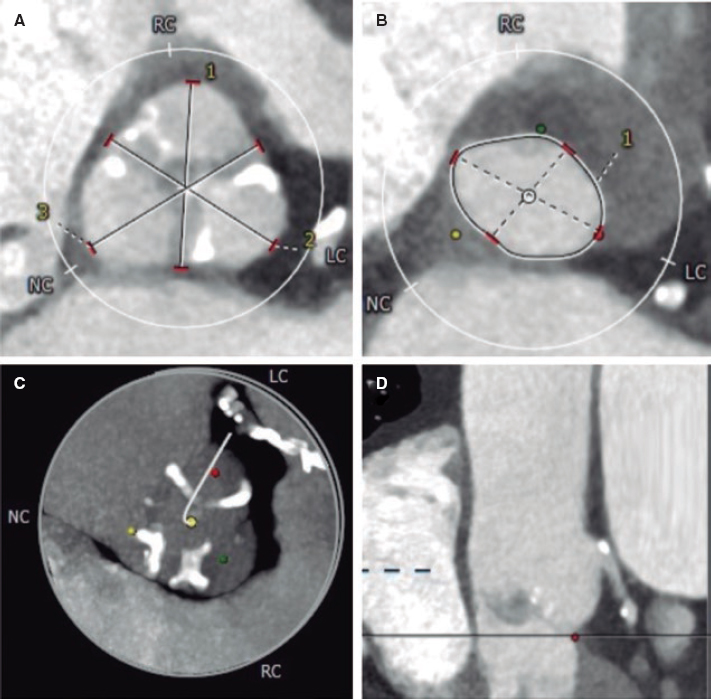

The characterization of the intracavitary mass. Both the echocardiographic description and the image acquired suggest the diagnosis of myxoma: 80% of them anchor to the left atrium and 16% develop embolic phenomena that are more common in large villous tumors (irregular and jelly-like, similar to the capture of the echocardiography shown).2 The main diagnostic doubt here has to do with the image of a thrombus. Different series recommend performing computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging or both before establishing differential diagnosis. In this case, given the general situation of the patient, we could consider completing the study of characterization by performing one transesophageal echocardiography. Although the definitive diagnosis is always histological with the study of the surgical piece, the analysis of the fragments extracted in the thrombectomy may help.

The neurologic prognosis is key to decide the therapeutic attitude. With the data provided by the computed tomography scan (and for the lack of data from the magnetic resonance imaging and the angiography, which by the way were difficult to perform considering the situation of the patient), it does not seem plausible to perform an invasive approach using the thrombectomy. Also, the hemorrhagic risk of a patient on ECMO contraindicates thrombolysis. Therefore, we can only maintain anticoagulation, establish anti-edema measures, and make thorough assessments to determine the patient’s neurological prognosis before indicating the surgical resection of the mass.

The management of a large mass that has become occluded and then caused a severe double mitral lesion that, in turn, jeopardizes hemodynamic instability should be urgent surgical resection. However, in a patient with refractory CS on ECMO, severe systolic dysfunction due to extensive ongoing acute myocardial infarction, and diffuse cerebral edema, the risk/benefit ratio should be taken into serious consideration. Several contemporary series on the surgical management of primary tumors recommend performing minimally invasive surgery,3 although in all of them patients with large tumors or hemodynamic instability have been excluded. Therefore, if the resection of the mass is to be performed, we should choose conventional surgery, in hypothermia with total cardiopulmonary arrest, and under neurological protective measures.

In sum, this is a complex case, one of those that do not see the inside of a clinical trial or that do not fall within the recommendations established by the clinical practice guidelines. It is not easy to establish this or that therapeutic attitude with a clear-cut image of the whole situation in a type of patient where the decision-making process has a lot to do with the evolution of the patient who also needs bedside monitoring. Common sense and the best clinical judgement should be the rule of thumb here. It will be very interesting to know the outcome.

REFERENCES

1. Basir M, Schreiber T, Dixon S, et al. Feasibility of early mechanical circulatory support in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock:The Detroit cardiogenic shock initiative. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;91:454-461.

2. Kalcic M, Bayam E, Guner A, et al. Evaluation of the potential predictors of embolism in patients with left atrial myxoma. Echocardiography. 2019;36:837-843.

3. Jawad K, Owais T, Feder S, et al. Two Decades of Contemporary Surgery of Primary Cardiac Tumors. Surg J. 2018;4:176-181.

Corresponding author: Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela, Avda. da Choupana s/n, 15706 Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña, Spain.

E-mail address: belcid77@hotmail.com (A.B. Cid Álvarez).